How could this war be prevented to be come off

I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones. - Albert Einstein

Since the ‘war to end all wars’ − as H G Wells so wrongly predicted a century ago − the world has seen the ‘peace to end all peace’ lead to the horrors of the second world war, proxy wars through the Cold War and, today, violent conflicts that increasingly affect civilians disproportionately and cross the red lines laid by the laws of armed conflict. The machinery of war and the available firepower has increased dramatically. The risks of a third world war are enormous. If we add in all the means and methods of warfare − conventional, nuclear, cyber, drones, and so on − we have the military potential to destroy ourselves entirely.

Violence is raging in the Middle East, Europe and Russia are poised on the edge of conflict over Ukraine, the United States is once more engaged in military action in Iraq and, as NATO pulls out, Afghanistan is vulnerable. Other flashpoints over disputed islands in the South China Sea, tensions on the Korean peninsula and over Kashmir are just some of the easily identified points of escalation.

In the past 100 years, we have, however, learned a great deal about how to prevent conflict. After the Second World War, we established the United Nations with the primary purpose of saving succeeding generations from the scourge of war. The European Union grew over decades from a trade treaty to an organization that won the Nobel Peace Prize for its part in transforming Europe from a continent of war to a continent of peace. NATO has had its part to play in shoring up the transatlantic alliance that bonded many European countries in a common cause. Today war between Germany and France is almost impossible to imagine.

Other regional organizations have been established in Africa, Asia, the South Pacific and the Americas. International bodies have been established to implement disarmament and security treaties and civil society expertise has been channeled through universities and think tanks − including Chatham House, conceived in 1919 with a view to preventing future wars.

According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, 254 armed conflicts have been fought since 1946 of which 114 are classed as wars (defined as more than one thousand battle-related deaths per annum). Since the end of the Cold War, the numbers of armed conflicts have dropped dramatically. Of the 33 armed conflicts listed in 2013, only seven were classed as wars – a 50 per cent reduction since 1989.

Many factors have supported the reduction in armed conflicts including the withering of proxy wars, UN sponsored peace processes and economic development. Research by the Human Security Report demonstrates that peace negotiations and cease-fire agreements reduce violent conflict even when they fail. Six peace agreements were signed in 2013 and four were agreed in 2012. Over recent years, despite common perceptions, we do seem to have learned how to create, keep and enforce the peace.

The laws of armed conflict and human rights laws along with the international criminal court, war crime tribunals, economic and military sanctions and domestic justice commissions serve to protect civilians. Although nuclear weapons possession or use, outlawed for most countries, are yet to be globally forbidden, international law has proscribed the possession and use of devastating weapons systems such as chemical and biological weapons, antipersonnel landmines, cluster munitions and blinding lasers.

Academic disciplines that study war and peace have developed a rich body of research that helps us understand how wars start and how they can be prevented or ended. No approach or system is perfect, of course, but we understand how resource scarcity, environmental change, economic stress, refugee flows and racism all fuel the engendering of conflict. We understand the importance of history and culture, the role of gender and the ways in which different political systems exacerbate or diminish the risks of conflict.

In a study for the European Strategy and Policy Analysis System (ESPAS), Chatham House and FRIDE predicted that the world in 2030 will be more fragile and governments and international institutions will struggle to cope with the twin trends of increased interdependence and greater fragmentation. Most significantly, we realized that the risks of inter-state wars are rising and a major inter-state war cannot be ruled out in the near future.

In the lead up to the First World War, many foolishly imagined that Europe was ‘too civilized’ to go to war. Prior to the Second World War people hoped that the aggression from Nazi Germany could be contained. In so many cases of war, we tend to be overly optimistic about the length of time (‘we’ll be home by Christmas’), the scale and the outcome of the conflict.

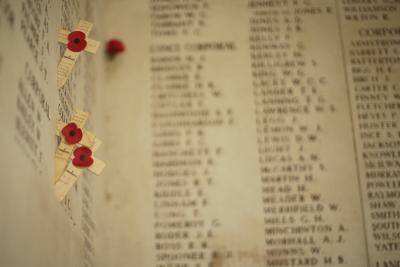

It is time that we put aside complacency and become more realistic about war and peace and ourselves. We know a great deal about how to prevent war. We owe it to all others who sacrificed their lives and families to put into action all that we have learned and ensure peace in Europe, the Middle East and Asia for forthcoming generations. Otherwise, there will be few left to hear our excuses.

Comments

Post a Comment